Mabel had known there would be silence.

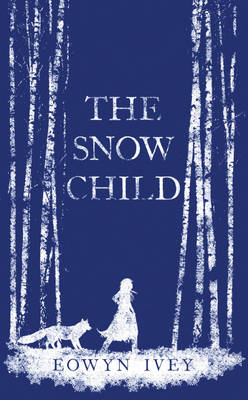

Mabel and Jack cannot have children. They move to Alaska to start a new life, one without the pressures of polite society. However it is not easy, the farm work is hard for her husband and money is tight. They struggle to survive the dark, cold winters and start to move apart. One night, as the snow falls, Mabel is overcome by a childish urge to make a snowman, no, a snow child. She gives it mittens and a hat and Jack carves a beautiful face in the ice. The next morning, the snow child is gone, but there is a trail of small footsteps leading into the woods.

Mabel and Jack cannot have children. They move to Alaska to start a new life, one without the pressures of polite society. However it is not easy, the farm work is hard for her husband and money is tight. They struggle to survive the dark, cold winters and start to move apart. One night, as the snow falls, Mabel is overcome by a childish urge to make a snowman, no, a snow child. She gives it mittens and a hat and Jack carves a beautiful face in the ice. The next morning, the snow child is gone, but there is a trail of small footsteps leading into the woods.

The Snow Child is a retelling of a Russian fairy tale, Snegurochka, Little Daughter of the Snow. Moved to the wild and isolated Alaskan frontier in the twenties, it beautifully describes the land, the snow and the hardships of making a living there. It does have a timeless feel to it, although mod-cons such as internet, air travel and daylight lamps have made living there much easier now, you get the sense that not a huge amount has changed.

So this was Alaska – raw, austere. A cabin of freshly peeled logs cut from the land, a patch of dirt and stumps for a yard, mountains that serrated the sky.

It still retains the feeling of a fairy tale though, perhaps this will not be to everyone’s tastes but I loved it. It is not fast paced, and it did seem to slow a little in the middle, if you tire easily of descriptions of snowy winter wonderlands and characters doing little but farming or hunting wild animals, you may struggle. The writing carried me through and I must admit to being fond of snow – we don’t get enough of the proper stuff here. The snow is so central to the book, it brings playfulness and beauty but also danger and cold.

What Mabel beheld in the snow took her breath away. The angel was so delicate, and its wings perfectly formed, like the print left on snow where a wild bird has taken flight.

The speech between the snow child and the other characters is lacking in quotation marks which added to the doubt of her existence or realness. When she is not present, the quotation marks return (thankfully, because I lose track without them). This side of the story reminded me of Raymond Briggs’ The Snowman and I kept expecting her to melt away to nothing.

After I’d read The Snow Child, I had a look round at other reviews and one reader criticised it for implying that all it takes is a child to make women happy. I’ll admit, I’m also annoyed by books that take that view but I don’t think this is one of them. It is not set in the modern day for starters and there was still the expectation for women to have a family. Mabel left behind her old life precisely to escape the peer pressure of society and the awkward conversations. Understandably she grieves the loss of potential motherhood, it is something she wanted for herself and near the end it explains the reasons for her wanting a child. They are simple and something that at the time, only a child could really fulfil. But it is not the snow child that cures her depression. At the start she waits at home all day waiting for her husband to return, her only responsibility is to cook. She feels useless and the long, dark nights of an Alaskan winter will cause depression in even the hardiest souls, let along with no distractions. She slowly comes out of her depression when she makes friends, socialises and starts doing tasks that make her useful and takes her mind off her previous life.

As I turned over the final page, I looked out my window. Our first snowfall had arrived. Magic.

The Snow Child is available in hardback and ebook editions and is published by Headline in the UK. Thanks go to Waterstones for providing me with a copy to review. This is Eowyn Ivey’s first novel and has been chosen as one of the Waterstones 11.

Related posts

4 Comments

Leave a ReplyCancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

I picked up a galley of this at Winter Institute a few weeks ago but I've not started it. This is one of the rare instances where I think I prefer the US cover to the UK one. I was already pre-disposed to like this book when I saw the author's name and then learned she's an indie bookseller in Alaska. Can't wait to get to the point where I can spend some time with this one!

I ordered this in at work recently. First off, the author is called Eowyn, so that is just awesome 🙂

But also the fairy tale aspect really appeals. it came in on Friday so I hope to get to it fairly soon.

I am hearing lots and lots of good reviews about this book here there and everywhere. I have it in the TBR but sometimes all the talk about a book can put me off, in this case (and with your review which is one of the most balanced I have read by the way) I am getting more and more intrigued. I shall read it soon.

Great review! I've heard amazing things about this one and can't wait to read it for myself!