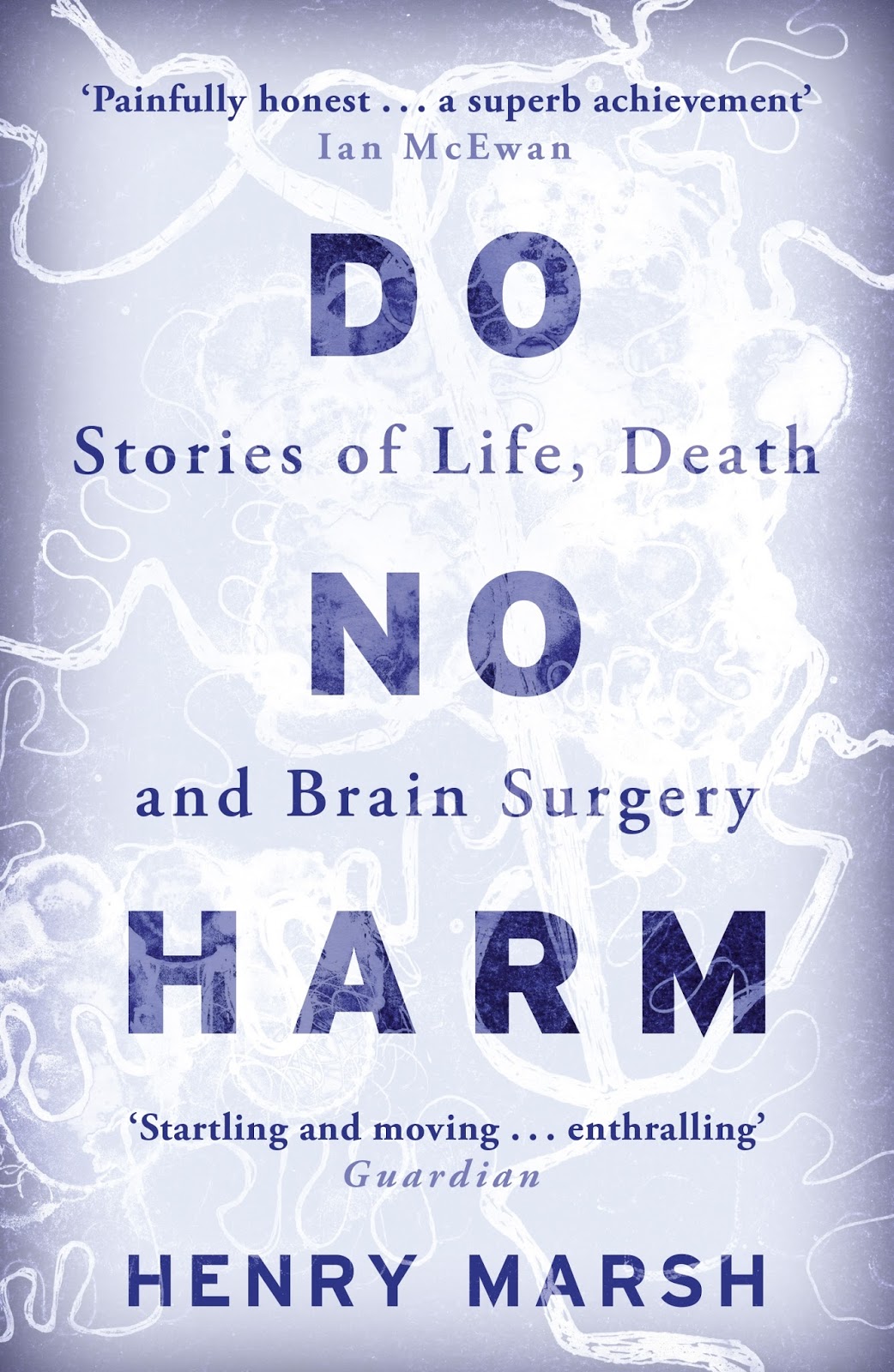

Every operation on the brain comes with great risks. The delicate organ inside our skulls holds our very selves, but one wrong cut can end in devastating results. We put a lot of faith in the doctors who wield the scalpels. But what is it really like for them? This open and very human account is an eye-opening glimpse into the world of brain surgery.

A book about brain surgery sounds like it might be hard-going or dry. Henry does have the advantage of a background in the humanities before he chose a career in medicine (they were different times) and I think this helps a great deal in the way the book is written. It is immensely accessible and full of honesty. He makes the point that all doctors are just people, and they get anxious or angry at times.

It does go into the details of several operations, so if you’re especially squeamish, you might want to avoid. After seeing many a fake brain exposed in medical dramas, it’s fascinating to read a about the real ins and outs of such things. The brain can’t feel pain for instance, it’s the pressure inside the skull that usually signals a problem in there. Not nearly as many surgeries are done whilst the patient is awake as television would have us believe.

If the operation succeeds the surgeon is a hero, but if it fails he is a villain.

What’s particularly terrifying is training new surgeons. You can’t really learn without practicing, and that means practicing on real people. Most trainees will stand in on operations done by their more experienced colleagues and get to lend a hand opening or closing the head (yes, as scary as that sounds) or doing simple bits of the operation. This can be risky and as Henry tells us, can end in disastrous results. On the other hand, some of the best surgeons are those who have learned from many mistakes in their careers operating on risky tumours.

Hypochondriacs beware. The bulk of the cases dealt with in the book are brain tumours and many of which start off with headaches. I guess it’s enough to get a little paranoid when your head hurts, but it helps to remember, these cases are from a lifetime’s career in a specialist subject. Brain tumours really aren’t all that common.

Henry’s dislike of the bureaucracy of the NHS leaks through in places. He’s seen a lot of change and a lot of frustrations. He shows the contrasts of his workplace with a private surgery, which he attends when he requires medical attention, but also the other side of the coin. He travelled to the Ukraine shortly after the fall of the Soviet Union and visited several hospitals, seeing how out of date and cramped conditions were. When he befriended Igor*, he helped bring in some improvements as well as operating on some more difficult cases.

*Honestly, I can’t think of a doctor called Igor without thinking of Discworld Igors or Count Duckula.

“I hope I never see you again,” she said.

“I quite understand,” I replied.

Goodreads | Amazon | Waterstones | Hive

Book Source: Purchased

Related posts

2 Comments

Leave a ReplyCancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

![[gifted] Elusive is the sequel to Scarlet by @genevievecogman1, set after an alternate French Revolution... but with VAMPIRES! 🧛🏻🧛🏻🧛🏻 My stop on the blog tour is Sunday, so please swing by to check out my full review. Otherwise Elusive is out on Thursday in the UK. Thanks TorUK / @panmacmillan for the review copy.

#bookstagram #booknerdigans #elusive #vampires #bookblogger #FrenchRevolution](https://www.curiositykilledthebookworm.net/wp-content/plugins/instagram-feed/img/placeholder.png)

Oh this needs to go straight on to the wishlist I think, great review love, thanks

Lainy http://www.alwaysreading.net

This is waaaaay high up on my wishlist, so maybe I'll go a-hunting for a copy in town this week. Thanks, as always, for taking the 'reading it first so I know I need to buy it' fall, haha. 🙂